Wed Nov 19 2025

In the study year of 2024/2025 I won 4 competitions in the courses of Jonas Skeppstedt at LTH (Lund’s Technical ‘Highscool’).

I wrote these 4 messages in discord, to clarify the methods+ideas that contributed to my victory.

Explanation: This was a competition in the course Multicore at LTH, trying to write the fastest 'preflow-relabel' algorithm

My thoughts on trying to win the competition: (skriven på engelska för att vara traditionsenlig) Some initial optimizations which proved necessary to win:

My first idea was to partition the nodes fairly to the the worker threads (To reduce cache misses, and reduce shared memory overhead). The worker threads themselves push and relabel their own nodes. The idea to partition the nodes proved unnecessary, as I barely had any cache misses (checked with valgrind). In my first working implemention of this, each thread had a ringbuffer, with atomic head and tail indicies. A worker thread would only take from it’s own ringbuffer, therefore, if it exchanged nodes in the ringbuffer with sentinel values starting from NR_NODES, and increasing, I could avoid the ABA problem. This way, I didn’t have to use locks. This was way to slow.

My next idea was even better. As cache wasn’t a concern, I wanted a global “worklist” which workers could take nodes from. This proved feasable and fast by having a global bitfield. For each node, we have a bit, 0 representing excess == 0 and 1 representing excess > 0. This was extremely efficient, as enqueue’ing nodes was a simple atomic_fetch_or, while a dequeue was atomic_swap(0), on the right u64 in the bitfield array. This way, a thread could receive a maximum of 64 nodes at once, which proved very efficient.

I actually did some measurements on this, and threads usually got around 15 nodes each dequeue. But I still had a problem when there was little work. Worker threads would just repeatedly scan the bitfield, ruining performance. I improved this by doing sleep(0) on failure at finding work. Other fun facts about this solution: I looked at Power8’s bit manipulation instructions, and found one that returns how many leading zeroes a u64 has (use __builtin_clzll with GCC). This was used to get the bits which were 1. This bitfield solution proved extremely fast, around 10x or 100x faster than my previous solutions. At this point I set all heights to 2, except those connected to sink (those are 1). (Though this didn’t actually improve performance)

I should also mention the incredible method of pushing flow without locks I came up with: First, for each node, store a u64 containing both the height and the excess of the node (courtesy of Felix). When you look at a neighbor, you first compare your heights. If you are + 1, you look at the edge and calculate how much you can push. Then, you perform an atomic_compare_exchange on the “other” ‘s u64 (containing height and excess), so if their height has changed (or anyone else has pushed to this node) the operation fails. After you succeed, you increase the edge flow as well. There’s a pretty nasty bug in this that never happens in practice. If you successfully compare_and_exchange, then the other node relabels 2 times and starts pushing it’s flow; the fact that you haven’t updated the edge flow yet might prove disastrous. This never happened in practice, as the compare_and_exchange and the atomic_fetch_add are neighbouring instructions. This bug that never happens could be solved with transactional memory though. Around this time, Felix generated a very nice graph, with 20 k nodes and the minimum cut in the middle of the graph. This graph was very challenging to all except my previous solution. (Still, this would all change with the Gap Heuristic) This graph was my point of reference for performance, also including huge001 and big002 from Skeppstedt. I made my own main.c which loaded in these files, and then made my preflow.c solve the graphs 2000 times in a row.

At this point I was very sure that I would win the competition, though this was completely false. This solution and all my previous one’s were not really relevant to the competition at all. After failing to implement BFS for a week (use a FIFO queue, not a FILO), I successfully made Global Relabel work, and this proved very important. Alve had found out that all the graphs 2000-4000 had minimum cut either at source or sink. This fact, combined with the graphs being absolutely massive, made it so performing Global Relabel before preflow was necessary to achieve performance.

As the competition had started, I had to rewrite my code to be called over and over by Skeppstedts main.c. I reused memory, only reallocing when necessary, and had a thread pool, kept in sync with barriers. Depending on the graph, different numbers of threads would be activated, and so on. I also tried setting thread affinity (which CPU’s should each thread reside on), which only made things worse on Power8. Unfortunately Hugo had a lead at this point, and I was very confused that my great solution wasn’t doing so well. Therefore I wrote a new solution involving the main thread doing pushes and relabels. These are mediated by secondary worker threads, who survey nodes with excess, and provide the main thread with array’s of valid edges to push on (and possibly how much you can push). In summary: the main thread just pushes and relabels, with barely any thought and valid edges are pre-computed. (For extra detail: All secondary workers have an atomic queue which the primary thread puts nodes into) An observant reader will realize that this solution could allow one node to push to another with the same height. Though it’s pretty easy to prove that this is still valid. I tried this solution, and it got basically the same score as my previous ones. This made me miserable, as any changes to the preflow algorithm didn’t seem to make a difference.

Anway, here I thought that Hugo would win the competition, as I didn’t have any more ideas. But Skeppstedt changed the rules, and gave you more time if you passed a certain number of graphs and so on. One of my previous solutions (not mentioned yet) was a single threaded one that kept track of node heights and did the Gap Heuristic. This solution was great on graphs with a more complicated minimum cut (orders of magnitude faster than all previous solutions). I tested this solution and was greatly surprised to get a score of 13000, clearing all the graphs. (My previous best was like 3500). Some facts about the graphs: 0-2000 are very easy. 2000-4000 are very brutal as they each have 25 k nodes, though minimum cut is always next to source or target. 4000-13000 have a more complicated minimum cut, yet have only around 1380 nodes, making them completely trivial with the Gap Heuristic. I learned this by watching in htop how many threads were running (the number of threads were dependent on the number of nodes)

At this point I had completely given up on all my smart multithreaded preflow solutions, as they didn’t allow accurate Gap Heuristic to be invoked precisely when needed.

Back to the competition, Skeppstedt deleted my score, and sought to use his more powerful Power computer in the competition. (So I had a 4 day break)

As the new Power computer went online I was initally very confused, as I only got 2900 when running normally, but when I looked at my code running with htop, I suddenly got 4009. This turned out the be a complete coincidence (probably). But what I realised was that the new Power computer had some interesting properties. I did some digging with commands such as lscpu, lshw… The new computer had 160 threads (or 20 cores with 8-way hyperthreading) with 4 NUMA nodes. Each NUMA node had 40 threads. The funny thing was, if Linux placed your threads on different NUMA nodes, the performance went down the drain. This was due to the huge overhead of sharing memory between NUMA nodes. This limited me to a maximum of 40 threads for the rest of the competition. So if you didn’t do the “Mapping” part, you got a huge variance in your scores, as Linux would place your threads willy nilly, without consideration for the NUMA nodes.

A nice observation could be made about the different ways of using these threads: If you had simple multithreaded code which did simple reads and writes with no atomic operations, you would want 5 threads, one on each core. Otherwise, the hyperthreading would ruin the performance, as threads would hinder each other. But, if you had multithreaded code which did expensive operations with a lot of waiting (atomics, ldarx, atomic_fetch_add), you would want to use all 40 threads.

Now in the competition, Hugo was in 1st place again. And because I had made so many different preflow solutions, I realized that preflow couldn’t be the bottleneck. It turned out that the graphs 2000-4000 were the bottleneck all along, specifically constructing the adjacency lists from the xedge_t *e input. My first naive way of multithreading this, was to partition the nodes among worker threads, let all workers read through the xedge_t array. A worker will only update it’s own nodes adjacency lists. To optimize this I had to come up with a mathematical formula using NR_NODES and NR_EDGES to compute how the nodes should be partitioned. (it used sqrt()) This put me in 1st place again. Though, with my ideas for optimization running dry, I, surprised that Hugo wasn’t doing Gap Heuristic, told him to use it. This put Hugo at 13285 with me at a measly 10259. So I was convinced Hugo would win, as I had no ideas left. In pure desperation, I did some actual time measurements, and realized that STILL, the graph construction of 2000-4000 took an enormous amount of time Much more than the preflow algorithm, which I had basically forgotten about at this time. At this point I was convinced that the preflow relabel algorithm was just a big red herring, the entire course centered around it, to make people lose focus of the real objective: To make graph construction fast.

I had basically given up. But one day I noticed someone (I assumed it was Hugo) using 0.4% memory in their solution. This was an absurd amount of memory to use (it also proved less optimal) but it made me rethink my graph construction algorithm. Instead of partitioning the nodes, I HAD to partition the xedge_t array. My first solution was to let the adjacency lists have an atomic length, which you’d atomic_fetch_add(1) when you wanted to add a edge. This is possible only if you allocate, for each node, the maximum possible adjacent nodes. Making me go up to 0.4% memory as well. With 40 threads, this solution was actually faster. Still Hugo was faster. atomic_fetch_add should really be banned on Power8. It translates to ll/sc in assembly, and is magnitudes slower than just a non-atomic load and a store (according to my measurements). So my next idea was to have multiple adjacency lists, to remove the shameful atomic_fetch_add. I had been avoiding multiple adjacency lists the entire competition, as I thought the concept extremely ugly (which it was). Still, with 4 worker threads (placed on their own cores, of course), each with their own adjacency list (realloced), I got even faster, to 13013. To improve cache behaviour for the main thread during Global Relabel and Preflow, I wanted to merge the adjacency lists into one. My first “clever” algorithm for this involved the worker threads cycling through separate partitions of the nodes, memcpying their adj lists into the primary adj list.

So for each partition, the workers would have to synchronize over a barrier. This was extremely stupid. And was slightly slower than before. So I rewrote it. The good way to solve it, was to directly partition the nodes among the workers, and then a worker will memcpy from all the secondary adj lists into the primary (of their nodes), no synchronization needed. This was faster and gave me the score 13187. (Very close to Hugo now) Desperate to close the gap between us, I looked at heat. Currently my main thread was using around 70% CPU while workers were using around 20% CPU. To distribute the heat more evenly I switched it up every so often, so different threads did Preflow. (This made the code extremely ugly) This improved performancy very marginally.

I also rounded out some allocations for optimal performance. Reallocing optimally and so on. Now my graph construction was very fast, and Global Relabel seemed to be a new bottleneck. My last optimization, that put me above Hugo, at nr 1 spot with a score of 13510, was very unusual. Usually when you do global relabel, you BFS from the sink, ignoring the source completely. But, if you include the source as a valid node (ensuring you reset it’s height to NR_NODES after GRL is done), some nodes will get less optimal heights (if they have a shorter path through source to sink, than straight to sink without source). Still, this is the optimization. I assume it’s faster, because super-accurate heights doesn’t actually matter all that much. Especially in Skeppstedt’s grapghs. Also, it allows the BFS to traverse (possibly) a lot less frontiers. Also, for my last submission I made my code extra ugly, turning most if statements into ternary (?) expressions (the comma operator (,) helps here) (Also remove {})

There’s other things I could discuss, like how I tried to parallelize BFS (not good idea, at least for this data), or how I made a height-ordered worklist (this is actually supposed to be really good according to the literature, but was too slow (You can actually implement it quite easily by letting each node have a “next” index and, for each height, having a starting index for that height …)) Another last second thought, when doing queues, you want to actually use real pointers and not indices, I used “start”, “end”, “head” and “tail” pointers to control my FIFO queues. My final solution was 552 lines. The branch of my final solution has 173 commits, though I have 10 branches.

TLDR: In preflow algorithm, do initial Global Relabel, also do precise gap heuristic (Yeet all nodes above height X when amount of nodes on height X goes to zero).

Use realloced arrays for all data.

Create graph’s adjacency lists in parallel without changing shared memory. Merge them efficiently (good paper on this).

Don’t use atomic_fetch_add (or any that rely on ll/sc (usually there is a faster way to do it))

Use FIFO queues

Don’t forget Mapping, Linux’s default thread affinity can’t be relied upon for consistent performance.

Explanation: This was a competition in the course Effective C at LTH, trying to write three different programs: A reverse polish notation calculator, a word frequency counter and a polynomial multiplier. The goal was to produce the smallest possible executable. I won

Here are conclusions from the mind bending memory efficiency competition:

The memory efficiency competition was about getting upset at GCC for doing unpredictable optimizations (GCC 10.2.0).

A key fact is that reordering completely independent statements will make GCC unlock better optimizations.

Also, reordering completely independent expressions separated by && or || in if statement, could appease GCC further (no, using (&) or (|) does not help).

A possible mistake is to spend large amounts of time just reordering code. This is wasted later when you improve the code functionally.

Never use “int”. GCC will try to overflow at 2^31, costing further instructions. Use “long”, which POWER8 supports natively (registers are 8 bytes …).

Use “putchar(char)” when outputting few characters (try this with ternary expression as char for optimal variable character output).

Favor static strings. Mutable strings (char a[]=“123”) require construction on the stack (use mutable strings for cool printf shenanigans, ternary format strings not recommended, neither is ignoring arguments with the * signifier).

Don’t use functions. Don’t use functions with more than 1 argument. Don’t use printf. When using printf, use “goto” to reuse printf. Don’t use scanf. Use strcmp.

When you have multiple separate loops, combine them into single loop. Generally merge all code together into big code yakuzi, where everything is done always.

When using stack for memory, create pointer and set to: address of itself, cast to long, add 0, subtract needed memory, cast to pointer.

When printing a long you want to use “%d” instead of “%ld”. This can be achieved by taking a “volatile void *” to your long, casting that to int * and dereferencing. This saves 1 byte.

Replacing all loops with goto’s does not reduce code size. Replacing if statements with ternary expressions does not reduce code size, though it does make the code look more optimal.

If function has annoying signature, redeclare function with better signature.

Using “stderr” or “environ” as free global variables does NOT work on POWER8 unfortunately.

Use as much memory as possible.

This was a competition in writing the MOST optimizing compiler (specifically, optimizing a single c file to produce as few instructions as possible). I won it with Alve.

Operator strength reduction or induction variable elimination, WITH linear test function replacement - didn’t improve cycles dramatically. I love Keith Cooper’s paper. SSA SCC’s are nifty.

List scheduling almost writes itself. Using ‘nr of dependencies’ as heuristic minimized stalls for ‘a.c’. Register pressure surges considerably, but thankfully Jonas has blessed us with 32 registers, saving us from spills 🙏 .

The ‘make intopt do scheduling’ method failed miserably for unknown reasons. Alve’s intopt doesn’t work and my own was too slow OR produced suboptimal solutions.

Register allocation + Loop invariant code motion WERE the most important. Alve implemented them.

Our opt.c has became unintelligible legacy code. Throw it in a dumpster fire.

This one was about making a bipartite graph maximum matching finder. I won with Alve again.

Graphs in forsete: 1 million nodes, 4 million edges.

Hopcroft-Karp is theoretically the best algorithm for the Maximum bipartite graph matching problem with a time complexity of O(E sqrt(V)), so we started with this algorithm. At first I tested some AI generated Hopcroft-Karp’s.

Chatgpt: 43

Grok: 46

(other’s like Claude were slower)

But Alve’s Hopcroft-Karp was the best with a score of 53.

Through some analysis we got that 99.968% of edges were being matched. This meant a large class of potential algorithms could be discarded.

We tried some initialization algorithms (greedy ways to set up the matchings before the correct algorithm starts), but found that none improved performance. (Not even Karp-Sipser).

The greatest paper which inspired us was “Multithreaded Algorithms for Maximum Matching in Bipartite Graphs” ‘https://www.cs.purdue.edu/homes/apothen/Papers/cardmatch-IPDPS12.pdf’. From this paper we learned of ‘Pothen-Fan+’, which won us the competition.

But ‘Alex Pothen’ (the master of Bipartite Graph matching algorithms) had published a more recent paper from 2017: “Computing Maximum Cardinality Matchings in Parallel on Bipartite Graphs via Tree-Grafting”: ‘https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1109/TPDS.2016.2546258’. It was generally much faster, but from their testing I saw that it was slower specifically for our type of graph. Also it seemed way harder to implement.

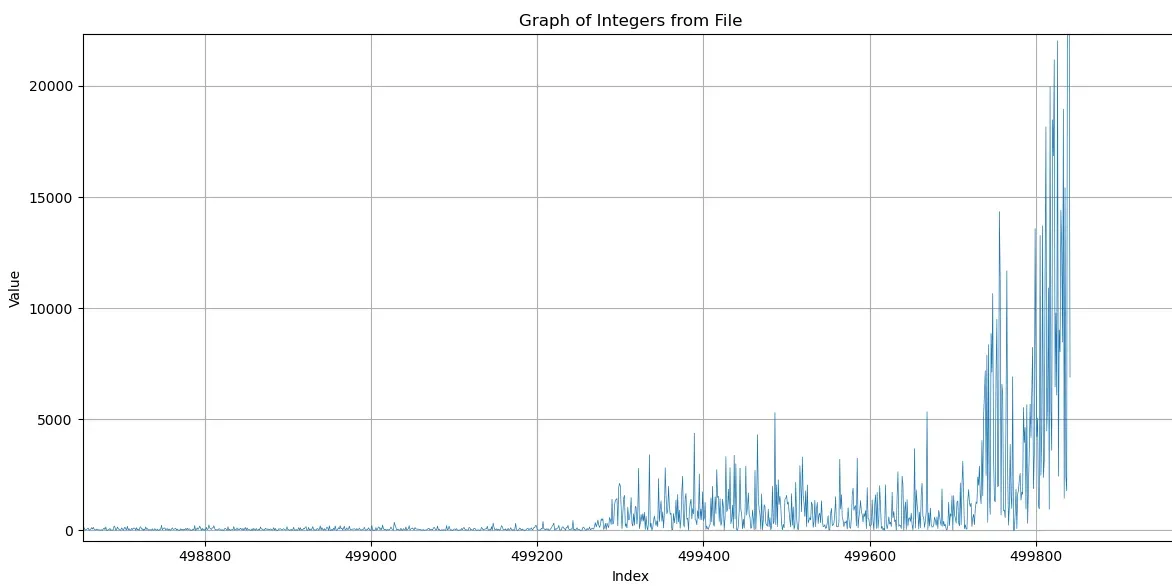

The rest of the papers we looked at were generally pretty bad. There were some ‘combinatorial algorithms’ which had lower theoretical time complexity. But I found no actual implementation of these on Github (and no pseudocode in their papers), so assumed they were a waste of time. ‘Pothen-Fan+’: This algorithm is the easiest to understand, the easiest to implement, and the fastest algorithm on the forsete graphs. Without multithreading, it basically just does a bunch of depth-first-searches to augment paths from unmatched nodes. It’s stupid. Single threaded it’s much worse than Hopcroft-Karp, as Hopcroft-Karp systematically finds augmenting paths with the smallest length first. Pothen-Fan+‘s paths will balloon to insane lengths, because it doesn’t choose them optimally. This is easy to multithread: just let multiple threads DFS simultaneously, but introduce one atomic boolean for each (right) node, to make their paths disjoint. Also: Pothen-Fan+ uses ‘fairness’, this means that you sometimes reverse the order of edges in nodes, to make the DFS explore different paths first. This was important.

With this I got the score 63.

Alve improved this to 75 by distributing work more efficiently among threads. For each iteration of Pothen-Fan+ he created a worklist of unmatched nodes, to distribute work less randomly. I increased this to 80 by changing the OpenMP schedule to ‘guided’ (Alves idea). As work was still pretty uneven (some nodes would be matched fast, while other nodes augmenting-paths went on forever) this redistributed work more efficiently to free threads. I wrote a pretty accurate ‘forsete-simulator’. It runs ‘matching’ on graphs generated live. You generate 4 million random edges and then remove duplicates - repeat til fixed point. Initially I tried having pre-generated graphs and sleep()‘ing a fixed amount measured from forsete. But this greatly increased variance in scores. With this very accurate forsete simulator, I found the maximum score to be 99.

My final score of 89 was achieved by parallelizing graph creation.

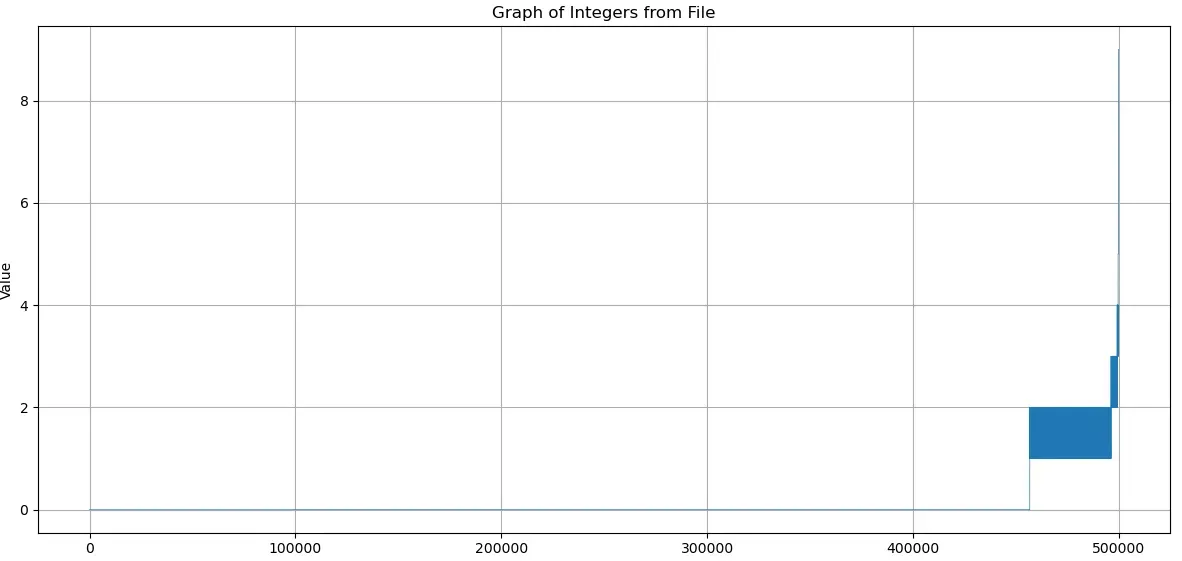

Then I wrote a bash script which called into Tristans FORZA forsete client, to repeatedly upload my solution to forsete. Unfortunately I never got a higher score. Though it was interesting to see that forsete really liked crashing on login. So I discontinued this strategy. Here are two graphs: The first is the length of augmenting-paths found with Hopcroft-Karp. The second is the same, but with Parallel-Pothen-Fan+: